Recently Antocularis had the opportunity to interview Kim Cascone, president of Silent Records in San Francisco. Silent is a dynamic record label and mail order service which Kim started out in the mid-eighties to serve the niche crowd of underground Industrial and electronic experimental music. Kim discussed many aspects of the business and how he operates a company of this caliber.

----------

AC- How did you get Silent Records started?

KC- Silent Records started in 1986 and it was an outgrowth of just putting out records by PGR. The first record by PGR was the thing that funded Silent Records. It did pretty well so we just took all the profits and the money made off the first PGR record and put it into a company that was going to release records of an experimental and Industrial nature. The first record that we released was a record by The Haters called "In The Shade Of Fire" and then after that there was Architect's Office and Organum, which was a split LP with Eddie Prevo, and then the company went on hold for about a year. Then we started up again in '89.

AC- Why did Silent Records go on hold?

KC- At that point I was becoming discouraged with the music scene in general, and at that time not many DJs were playing Industrial music. There was like a dip, I don't know what was happening, but college radio was changing. It was going through a little period of change and growth at that point so I think a lot of the DJs that were playing this kind of music were either graduating or getting kicked off the staff to be replaced by specialty things like World Music, or Women's Music, stuff like that. Then all of a sudden there was sort of a resurgence. I think with the popularity of Wax Trax fans and stuff like that a lot of Industrial music sort of rode in on the coat-tails of that genre.

AC- PGR was the first group that you were involved in?

KC- In San Francisco, yeah. Well, I mean it's the first real project I was involved in.

AC- How did that develop?

KC- I was working on a project called Language Lab which was sort of an improvised electronic ensemble and one of the members and myself split off from that group and formed PGR.

AC- How long has PGR been around?

KC- I think we started it in the spring of '84.

AC- Has PGR been successful?

KC- Yeah.

AC- What are some of the things that Silent Records offers to the public?

KC- Well, we offer records and CDs to our customers, that's one thing. It started out primarily as a label, so we were releasing records at that time. From that point on we discovered we couldn't make enough to keep things floating with just being a label. Because in that situation you're basically selling on a 90 day consignment to distributors, who usually take 120 or more to pay. So you're always reliant on that 90 to 120 day cash cycle and you can't do that. You need a steady income. So that was another reason why I decided to put Silent Records to rest for about a year. I needed to regroup as far as our strategy, so after that the first thing we did to diversify our cash flow was to start a mail order operation. Which as it turned out proved to be very successful. We're getting anywhere from five to ten percent response from our catalog mailings which was phenomenal. And at the suggestion of my lawyer I started a distribution arm in 1991. In January we officially started "Silent Distribution." So that's some of the things we offer to our customers. Our customers are pretty much either distributors, flesh and blood, or retail stores.

AC- Most of the types or kinds of music that Silent Records carries could be categorized as-

KC- It depends. In our catalog we cover everything from Grindcore to Musique Concrete to Ambient to... I mean everything that has become a hybrid of some sort out of the Industrial culture, we carry. Even Grindcore has roots in the Industrial culture.

AC- When Silent Records began, what were the types of music that were available to you then compared to now?

KC- Well, when we started Silent Records we didn't do a lot of distribution. We were concentrating on our own releases at that point. It wasn't until I fired the company back up that we even considered handling other records, by other artists. In the beginning it was strictly just finding artists to release records by. As we progressed we got into distributing other people's stuff, so we did our own stuff less. I mean the frequency became less. It was like we put out a record and it was successful so we said, "Why not start a record company?" We started a record company and then we found we couldn't really make it float, depending on the distributors to pay who were famous for not paying. We had to be inventive with other ways to make the business work.

AC- The first band that you put out, The Haters, were you involved in that personally?

KC- No, that was... at the time I was on tour in Colorado. We were playing the Erotic Arts Festival in Denver and I met The Haters. We just became friendly and everything. He had some music that he wanted to put on record and I said let's do it. That's pretty much how it came about. That's really how it started in the beginning. There were no contracts. It was very loose. I think that when you start dealing with people like who we're dealing with now like Controlled Bleeding, or Legendary Pink Dots... these people are selling records in the upwards of you know, five K or so. You have to do things a bit more professionally and as you get further into a business you discover that you can't just keep doing business the same way or else you stay at a certain level. So we discovered that we had to offer contracts to people and become more professional.

AC- Who are some of the people you've offered contracts to recently?

KC- Well, I'm not at liberty to discuss projects that are coming up. Two people that may be recording something, or releasing something on Silent might be Controlled Bleeding and Legendary Pink Dots. That would be great, but that's not firmed up.

AC- Besides The Hafler Trio, what other groups have you released on Silent in the past?

KC- The Haters, Architect's Office, Organum, PGR, and Thessalonians.

AC- What are some of the things that has made Silent Records a success?

KC- I think the first thing that helps in making any operation successful is just your professionalism, and that encompasses a lot of different areas. I think number one having a lawyer, having an accountant, takes some of the burden off of me and it also hands that area of things over to people who have expertise in it. So I think it's very important with people who start businesses is that they have to learn to accept their own shortcomings and to delegate things to people who have talents in specific areas. That's one thing. I think our sales force now is really instrumental in punching up the cash flow for us right now. We have three salesmen now who work five days a week doing nothing but calling retail stores. Our MCI bill is getting heavier and heavier every month.

AC- Because you are focusing more on the business aspect of Silent Records, do you think it's dampening-

KC- I know what you're saying, yes and no. I've been tossing that around lately and feeling like... you have to be careful... that's a good question. It's very easy to get sucked into the whole business side of things because it can be all-consuming. You have to be very careful to keep your priorities straight. The focus is the music, it isn't running a business. That's sort of a by-product of your goal. You have to be able to run a business in order to achieve that goal. So it's like anything else. If you want to drive a nail, you have to use a hammer. In order to put out a record, you need to have business operations put in place in order to get that task done efficiently. The business end of it becomes a tool. You have to learn how to use those tools well in order to be successful, to hammer the nail so it's flush and it's not all crooked. I mean you have to learn how to do things.

AC- It could also be a double-edged sword. A hindrance.

KC- It can be, and that's the down side of running a business is that it can be all-consuming. It takes a lot of work, a lot of vision, it takes a lot of patience. People get caught in wanting things NOW. They want everything instantaneously and the other thing that people get caught in is greed. I think that's why a lot of distributors (NMDS, Rough Trade) that have fallen in the past few years have fallen into the trap of greed.

AC- Trying to make even more money off the whole deal-

KC- Well, it's weird. It's kind of like these distributors got caught behind or between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand they are accepting stuff, goods from bands and artists on consignment which means they don't pay for material up front. They say, "We'll pay you in 60 to 90 days." They turn around and they give this same material to stores and they give these stores terms. They say "You can pay US in 60 to 90 days." Well, it's a pyramid scheme and what happens is when they start getting cash in it never goes to the artists. That's a major complaint, right? So what it starts doing is accumulating in their little pool and then they start doing projects, or paying... they all of a sudden start finding all of this money that's pooled up and they go, "Oh wow. Wouldn't it be great to have a Macintosh? That would make things a lot easier, and jeez, you know that beat-up Volkswagen of mine... I don't know." And, "We should hire somebody to do this. I can't stand having to drag the mail to the post office every day." So the money that's coming in is now being pissed out in expenses. What we have done (we picked this up from someone else), we don't offer stores terms. I mean that's the most dangerous thing you can start doing. Unless you are dealing with chains who are going to be around, but the independent Mom and Pop's, they open and close quicker than bands come and go. So you really have to be careful. We have a cash up-front policy with 100% return. So if something is not selling or it's you know, hanging out on the shelf or whatever, they don't want it anymore they are free to return it and we'll refund their money.

AC- Is that sort of a deal hard to work out with retail stores?

KC- With some stores it is, because they don't want to pay for anything up-front. They want to be able to sell it on their end first, get the cash and meet their bills at the end of the month.

AC- Is that the norm of the industry?

KC- It used to be. I think it's changing. I think more independent distributors are finding that depending on what their niche is, they can demand cash up-front. So stores really have to budget for that in advance, rather than paying things at the end of the month. They form a budget for a particular type of music whether it be Reggae or Women's Music, or Industrial, and they say, "Okay I'm going to allot myself $200 this month to pay for that section of my store." Then they go ahead and place an order with a distributor who specializes in that music and they make their payment.

AC- Are there many retail stores in San Francisco that go "Oh, it's Silent Records. Yeah sure, we'll take the stuff." Automatically?

KC- I don't know about a lot in San Francisco, I know that there are a few like Amoeba in the east bay and Auricular Records in S.F. people like that who-

AC- Just trust your judgment.

KC- Right. And we do have accounts across the U.S. like Zed Records in Long Beach and Rhino in L.A., Wax Trax in Chicago. We have some big accounts that say, "Send us whatever." That's sort of an exaggeration. I mean they do look over lists that we send them but there are actually one or two stores that just say, "We don't know a lot about this music. Pick out ten albums that you think would sell well in my store." So we do that on occasion.

AC- Getting back to the early years of Silent, how did you get involved with groups like Architect's Office etc.?

KC- Well, again we were traveling in Colorado we met up with Joel from Architect's Office and The Haters, and Kelly from Human Head Transplant-

AC- So this was all part of the Erotic Arts Festival?

KC- Yeah. There was actually two or three gigs that surrounded the Erotic Arts Festival. So it was like a little pow-wow of the Industrial crowd. Tribes that were meeting. Very strange because at that time (this was 1986), the Crowley thing was really peaking so there was a very heavy emphasis on Crowley/Psychic Youth kinda stuff. It was very interesting to be in a small community that you would never have guessed existed with people who are like way into Genesis P. Orridge and the whole Psychic Youth thing.

AC- How was the Industrial scene evolving from that point, in the early years?

KC- It was very odd. I moved here (San Francisco) from New York in '83 and I knew nothing about Industrial music at that point. At that time I was playing free music, like improvised music with people like Leslie Delaba, you know, people who were associated loosely with the whole downtown improv scene. So when I moved out here... my background is also in electronic music, I've been to school and all that. It's baggage but it also helped out a lot. Anyway, when I first moved out here I didn't know anything about Industrial music and I was playing with Language Lab and this guy had a little practice studio in Oakland on Telegraph I think it was. It was in a really bad neighborhood and we had to get in there late and sort of sneak in with our equipment and whatnot. Very interesting beginnings. He was remodeling his living space which was in the back. Apparently somebody had left a Re-Search magazine, you know the Industrial culture stuff, and it had fallen into water or something or the bathroom had flooded. He had put it on top of a radiator to dry it out. So we had this ballooned-up sort of book and we were reading through this weird shit like Monte Cazazza and all this bizarre stuff, Throbbing Gristle. A lot of this stuff was brand spanking new to me. I had no idea this stuff was going on. I became fascinated because it was like, "Wow, there is sort of a mixture of electronic music on a grassroots level that's mixing with a punk aesthetic." That whole thing intrigued me because I was so sick of the pseudo-academic stuff that was going on.

AC- Electronic music was being dominated by all of it.

KC- Exactly. Unless you had a studio in a university or something, it was very hard to create and market this kind of stuff unless other university professors were buying it.

AC- Did you ever meet up with some of the early Industrialists like Monte Cazazza?

KC- Yeah. I know Monte Cazazza. I've met Mark Pauline a few times, and at that point it was very strange. The community was so small and things were happening on a real grassroots level that you just knew a lot of people.

AC- As opposed to now-

KC- Well, Monte just signed to Mute Records. I mean they're reissuing a lot of the back catalog stuff by SPK, NON, Monte Cazazza, The Hafler Trio. Mute's very smart. I think they're paving the way in making stuff easier for a lot of independents right now. But in the very beginning the scene was very small. It was based in lofts and performance spaces. That was about it. You could tell there were people who were involved in it, and you know who they were. You had people like Chris Force and the whole 455 space.

AC- I've been hearing a lot about the 455 lately. What was it, just a venue?

KC- Yeah. Not real early. I think it started about '87 or so. At that time the A.T.A. gallery had burned down and they hadn't really found a new place yet. Some kids who were very much involved with bands like... oh God, what was the name of their... I can't remember the name of their little project, but basically it was formed very loosely around the whole Crowley thing once again, Psychic Youth and that kind of stuff. So these kids found this space on 10th St. and they just rented it. It was like $750 a month or something and they had a place upstairs that they could all live in and the downstairs was a performance area. So when the A.T.A. space went down I was doing a series of concerts at the A.T.A. gallery called "Noise Knocked" and it was basically a monthly series that was dedicated to Industrial culture, or noise, or whatever you want to call it.

AC- Were there a lot of bands involved in that project?

KC- Oh yeah. Every month it was a new band, or a bunch of bands. When the A.T.A. burned down I had no place to put them on, so I transferred it all over to the 455 space, and held about 2 or 3 there.

AC- So you were acting as a promoter back then?

KC- Yeah.

AC- Which eventually led into a record label.

KC- I think I was doing it about the same time as the promotion stuff. The promotional thing I was losing money on. At that time my financial status changed because I went from working full time to working part time, so I couldn't absorb the costs anymore.

AC- What is your knowledge of Musique Concrete?

KC- Musique Concrete was a term coined by French composers Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer. They both sort of helped coin this term back in the days when tape was a new medium. This was post World War II. When reel to reel tape came along they found they could manipulate sounds by basically editing. So it became like almost editing a movie. Except that you were editing sound. So now they had a malleable medium, they were able to reverse sounds, they were able to actually physically stretch the tapes sometimes and cut off parts of sounds and mix sounds and perform an audio montage type thing.

AC- Similar to what is going on with video right now.

KC- Right. I think that the whole thing with video has been happening very slowly over the past 20 years. A lot of the new American filmmakers like Stan Brackidge and Kenneth Anger and people like that were very instrumental in paving the way for a lot of the current video. You know, hand held stuff and using different textures in the backgrounds, collage type stuff. I mean there has always been that Avant-garde underground that's been sucked up by mass media, and the same thing happened with Musique Concrete, and Rap, and stuff like that where it (mass media) said, "Oh that's very interesting. We can USE that." With samplers it was the perfect medium. You didn't have to cut anything. You'd just sample and it was a lot easier. So the immediacy of stealing was very-

AC- (Laughs)

KC- Well, yeah. Before I get myself too deep...

AC- How do you think Musique Concrete relates to the Industrial music of today?

KC- The progression there I think... you have to remember that all through this period Cage was still working and professing that sounds around him were music, and that there was no reason to separate pitched, melodic based quote-un-quote sounds music. There was no reason to separate that from the sounds we hear outside everyday. So, he was very helpful in creating the groundwork that a lot of this stuff took place in. When Musique Concrete happened in the 1950s, there were other fusions happening at that time too. They progressed in universities up to a certain point, and then all of a sudden when rock and roll started, there was another hybrid. You can go back and find, I think it was Pierre Henry that did a rock opera with Spooky Tooth. There was some very bizarre collaborations back then. Of course you had Frank Zappa and you had groups like Pink Floyd. Then Germany spawned a whole group of bizarres, Tangerine Dream, Ashra Temple, Guru Guru, all of these bands that had taken the ideas of Stockhausen and Cage and just sort of co-opted them and used them in their own music. So that's where rock and popular cultures started borrowing from the academic world and the mixture caught on. And the 1960s of course were well-steeped in all kinds of psycho active drugs and enhanced that experience. Then the imagination was fuelled and it got crazy. The whole psychedelic movement. You can listen to early Pink Floyd or Jefferson Airplane or the Grateful Dead, and they all used those things on their records. Using sounds and strange instruments. Phil Lesh of the Dead was an avant-garde composer. He had written pieces for three orchestras playing simultaneously. He did a very underground kind of cult record called "Sea Stones." I can't remember the other composer he worked with, but that was like all electronic music. George Harrison recorded an album of all electronic music. What you really need to do is pick up a book about electronic music and just sit in awe of people who were doing things back in the 1920s and 30s.

AC- I remember reading about a Musique Concrete artist that lined the entire inside ceiling of an auditorium with 500 speakers and composed a piece of work just for the auditorium.

KC- That was Iannis Xenakis, and it was in Brussels. The speakers were all kind of... the piece had been recorded, all the different channels were being fed to different parts of the room to different speakers. So you'd have these cluster movements of sound going from one end of the room to the other, just based on his mathematical plotting of density. They sweated it real hard to try to get that stuff to work with the technology that was available back then.

AC- I've heard rumors about a group of Musique Concrete artists in Russia that existed back in the 1920s and 30s, before the French school of the 1950s.

KC- They had wire recorders, and they also recorded onto optical film. So there were some composers who were working with wire, which was difficult because you could only get so accurate with wire. And with optical it was similar, you had to visually kind of edit. You couldn't really run it at speed through the projector. They developed their techniques on how to cut and paste sounds.

AC- Did any of that stuff survive and get onto stable recorded media?

KC- Some stuff has survived. I'm not real sure out of a lot of different composers whose work has survived. It's hard to say. I don't know where it would be, or if it's reissued or what have you. Some of the Dada and Futurist stuff has survived and has been re-released. As far as the wire and optical stuff, it's hard to say.

AC- Do you carry any of this original Musique Concrete on Silent?

KC- No.

AC- Some of the material you have is neo-Musique Concrete though?

KC- Pretty much so. We're only interested right now in stuff that touches on the Industrial culture. The stuff that is earlier is more academic and I think that unfortunately-

AC- What do you mean when you say it was "Academic?"

KC- Academic meaning that it was all based in universities and that kind of thing. Where there were university professors or it was attatched to a university. That's where a lot of this music came out of, was the whole academic world. It was not pop culture like what we have today. That kind of thing did not exist back then. If it was experimental or ground breaking it usually emanated from universities or centers of learning.

AC- Like with art. That's why it is always referred to as a "school."

KC- Exactly. What helped that in Europe though was that they teamed up with the state run radio stations. So that's where a lot of these schools quote-un-quote had formed. Kind of a hybrid of state operated radio stations and institutions of higher learning. People who were eager to start an electronic music studio often had to go to a place that was technically equipped, which at that time was only radio stations. That's why the ROTF in France was where Schaeffer and Henry were based.

AC- And thus began college radio (Laughs).

KC- Probably.

AC- Do your personal music tastes differ from what Silent Records carries, or is it one and the same?

KC- It's one in the same. I think that mostly... I have a lot of different interests as far as music goes. I like Classical, Rap, House Music, Jazz, I like a lot of different types of music. But it's not the field I have an expertise in. Since my background is in electronic music, which lended itself very nicely to the aesthetics involved in Industrial music, and I've been involved with this music for close to 20 years now. It's like my field of expertise.

AC- Are you solely responsible for what Silent Records decides to carry?

KC- I'm the president. I pretty much navigate the label as far as where we go. Then we have a staff of people who help in business and bookkeeping.

AC- Do you have people working in the field as scouts, to bring bands to your attention?

KC- No, I don't need people to do that (laughs). The bands present themselves quite nicely. I get tons of demo tapes. I think that at this point I pretty much know who we want to get on the label. Unknown bands don't sell a lot of records, unfortunately. You have to be careful about what you release.

AC- That's too bad.

KC- It is and it isn't. If a band has a certain kind of sound that you know is going to catch on, like there's a group from Australia that we might be doing a CD with called The Pelican Daughters. Nobody in the States has heard of them, but I really like them and I think they would be very popular here. Occasionally there are bands who are unknowns that we'll take a risk on, but it's dangerous. We took a risk on Architect's Office and we're still sitting around with 200 records or so. It took a long time to sell those 800 records. That's why we're trying to go with more visible projects, and create a contact sensitive image or identity to the public so that at a certain point whatever comes out on Silent Records will have that air about it. It's like Wax Trax. You know, a new band comes out on Wax Trax it's like, "Oh, wow! It's got to be good." It takes a while to build up that aura. So that whatever we release people go, "That must be interesting. Let's buy it, it's on Silent Records."

AC- Is that one of Silent Records' primary goals right now?

KC- I think in a way it is. That's not a forefront goal. It's just something that we are trying to develop along the way. You can't force something like that to happen, you have to day by day keep presenting yourself to the public as people who are interested in interesting things and when it gets drilled in and you create a context like that, then whatever comes out on the label will be considered interesting despite virtue of being associated with it. The goals we have now are more mechanical goals. Expanding our office, painting the walls, where the money is going to come from for the extra desks, really boring kinda mundane stuff like that.

AC- How did you come up with the name "Silent Records"?

KC- Well, the first record that PGR put out was called "Silence" and that was sort of an homage to John Cage. So the entire company is sort of an homage to John Cage (laughs), in a way. I also thought it was very Zen-like at that point. Plus, at that time the British harsh power electronics like Whitehouse, was very popular. The people I was hanging around with back then were very into that. So, it's sort of a contrast to that. I wanted to do something not noise, not Industrial, and I wanted it to be Silent. People always ask me this stupid thing, I go into a bank and they go "How do you make Silent Records?"

AC- (Laughs)

KC- So it's something that people will remember. I was at a wedding recently, and I was talking with a person, you know, just as you do at weddings and they don't know anything. They're just normal everyday suburban people and he asked me what I did and everything and I said, "I operate a record company", and he goes, "Oh, that's great. What's the name of it?" "It's Silent." I was standing in a group of about four people, and he went "Hmmmm. That's interesting." So maybe he won't forget.

AC- So the naming of the company was eluding to things you were specifically interested in doing?

KC- In a way, I didn't want to be pegged as Industrial. I really hated that at first because the first, actually second grouping of PGR was very Industrial in it's sound. At that time I was working with a guy who was very much into Throbbing Gristle, Whitehouse, and stuff like that. I found very quickly that a lot of the music that was happening was based in... it seemed like it was too easy. It seemed like if you had a short wave radio and 12 delays and some autopsy photos, you could put out a cassette. I became very anti-Industrial for a brief amount of time. Only because it seemed that there were so many people doing cassettes, and so many people were just working in their bedrooms turning out this swill that was just horrible. It wasn't imaginative, it was just-

AC- Do you feel it was becoming stagnant?

KC- Very much so. Oh God, very much so. I mean the whole cassette networking thing just grew geometrically to a point... I have four milk crates of cassettes that are basically demo tapes of people. It just got to a point where I just threw them in the box. I couldn't even listen to them.

AC- Has Industrial music finally come out of that stagnant period?

KC- It has, and it's changed a lot. I mean from when I first started working in it to now. Controlled Bleeding, whose a colleague of mine is now signing with a major label. It's very bizarre. I mean I would've never guessed that when I first heard Controlled Bleeding. But I'm happy for them and I think it's really great. I think the thing that was really instrumental in a lot of bands proving their seriousness was the few artists that broke away from cassette media, and I think that was very important. That was something that my colleague who was working with me in the very beginning... I can thank him a million times for this. He says, "No more cassettes. Let's put out an LP. We have to prove how serious we are." I kept thinking, well why? Cassettes are okay. We're having fun, right? He was like, "No. That's bullshit. Let's put out a record." So we did, and it was like night and day. The kind of acceptance that we had because we were on vinyl was just amazing. But again I think that really helped push the movement forward. And then when CDs came along it was just one step further. The people who were very serious, who took their work seriously, they weren't going to release anything on CD unless they made sure it was their best work and that a lot of effort and thought went into the packaging. So that really separated the wheat from the chaff very early on. And it became an industry. That was the other thing. It stopped being networking only. It started to be people's livelihood. Look at Genesis P. Orridge. Look at Graeme Revell. These people went on to make some money at it.

AC- Where do you see Industrial music progressing to now?

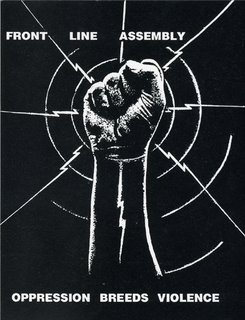

KC- A million different ways. I think as in any genre you're going to have little offshoots and inner distinct sounds that happen. I think unfortunately the big push with Industrial has been the whole Nettwerk/Wax Trax thing. So anytime I talk to somebody who is sort of new in this whole scene I say, "Well, we deal with Industrial music." And they go, "Oh. You mean like Skinny Puppy." It's interesting how people have co-opted the term Industrial to mean Industrial-dance. So Industrial music right now has a lot of different inner hybrids. Like there's ambient-Industrial, there's a new thing coming up called ethno-Industrial, like Muslimgauze. Where's it all going? I have no idea. There's a million little schools. You have the European Industrial... and they're not even calling themselves Industrial anymore. Unfortunately, it's just a name we've been stuck with. I hated it for a while and then I just said, "Get used to it." If that's what we are, that's what we are.

AC- I would like to know how you got involved with The Hafler Trio.

KC- Well, I was writing to Andrew Mackenzie about a year and a half ago and I was asking him if he would be interested in doing a project for Silent at some point. We just stayed in correspondence. At that point he was involved in some other projects and he said "Well it depends. Make me an offer." I really didn't know what to offer him. We just stayed in contact loosely. When he came to the States I met with him here and at that point what happened was, "Kill The King" was something that was going to be released on a label in Sweden but the label folded. Went bankrupt, which wasn't a good omen at all. We decided to ignore that. He was shopping this around to various labels in the States. So I said that we'd be interested in doing it, and I needed to get some sort of an idea of what it would take to buy out the Swedish company from this project (not to buy the Swedish company). He basically said that there was printing in Amsterdam that needed to be paid for, and there was a master residing in a pressing plant in Germany. At that point I found the project to be way expensive. It was going to cost us about $7 per just to get into this. Staalplaat became interested in the project and we worked everything out between the three of us. It was a co-release between Silent and Staalplaat. So, Mackenzie and I were in constant contact with one another via fax. We are working on some future projects.

AC- The history behind The Hafler Trio seems somewhat cloudy. Are you familiar with it?

KC- My memory of it is that it started about 1984 with Chris Watson, who was an ex-member of Cabaret Voltaire. Well, Andrew and Chris have had sort of a falling out and it's gotten to a legal stage at this point. Anyway, I don't know what the outcome of it will be, but it's common with people who have worked as partners. It's like a bad marriage. You get a divorce. So Chris went on his way, but Andrew continued with The Hafler Trio and released stuff that he basically authored. Through the years they grew from a little project that was just doing stuff on compilations on some of the more well known Industrial labels throughout Europe and continued to put out albums occasionally when they could. They have actually been very prolific. He's got a good amount of material out there.

AC- There was an article in the last issue of Ipso Facto that stated there was an earlier stage of The Hafler Trio that had some scientists working as members in the group.

KC- It was kind of a way of dealing with media manipulation. Andrew created this whole mythology based around the scientist Robert Spridgeon. It's all B.S. pretty much. But it was amazing how many people believed this for years, you know. I mean I even believed it when it first started coming out. In my own research I looked for something by Robert Spridgeon because I like to frequent used book stores. Wherever I am, I go into used book stores. I've looked for stuff for years by Robert Spridgeon. I mean I've cross-indexed, I've looked in bibliographies, I have done extensive research on anything by Robert Spridgeon, until I started to realize that this was all a bunch of crap. So it dawned on me that there was no Robert Spridgeon, there was no Edward Moolenbeak, none of these people existed. Andrew's the kind of guy... Andrew loves to play with people's heads. That's what I love about him. He'll present this information and then you'll find out later that it's the very opposite of what it seems. And he does that with his music too. I think it's very interesting.

----------

This interview originally appeared in Antocularis issue #2. January, 1993. For more information about Silent Records artists and releases please visit

http://www.silentrecords.net/

----------

----------